My Punk Rock Past, and How It Drives Me Today

In wisdom gathered over time I have found that every experience is a form of exploration.

—Ansel Adams

Now that my book has been released, several of my friends (and my agent) have advised me to get out there, informing me that it is personality that sells a book. It’s fortunate that after 70 years of living, I have a complete personality in place, with no need to create a new one.

I grew up an only child in an Air Force family. As an infant I was brought to Taiwan by my parents, and I spent a couple of years under the care of a young Taiwanese nanny named Abi. Then I was abruptly moved back to the States, and cared for by my mother—who was as sweet as could be, but not very physically affectionate. (When I was in psychiatric training, I spent a couple of years in therapy working on that issue. No telling how much that f***ed me up!)

From then on, every 2 or 3 years we would move around the country from one Air Force base to another, until my Dad retired when I was twelve. We then settled in Houston, where I could start junior high, and my Dad could work as an engineer at NASA during the Apollo program’s lunar missions. After being a proverbial “Air Force brat” throughout my younger years, I spent the next six years in the company of other “NASA brats.” (We weren’t that good at sports, but very good at science fairs!)

After graduating from high school, I pursued a bachelor’s degree in biology and social sciences at Rice University. I then completed both medical school and psychiatric training at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio. I worked for state-affiliated outpatient services in Austin for about 11 years, and then practiced “frontier psychiatry” in the scenic Big Bend area of West Texas for several wonderful years. Since 2001, I’ve been providing both inpatient and outpatient services for MaineGeneral Health, based in Augusta, Maine–where I’ve been supported in my efforts to promote the reform of modern psychiatric practice.

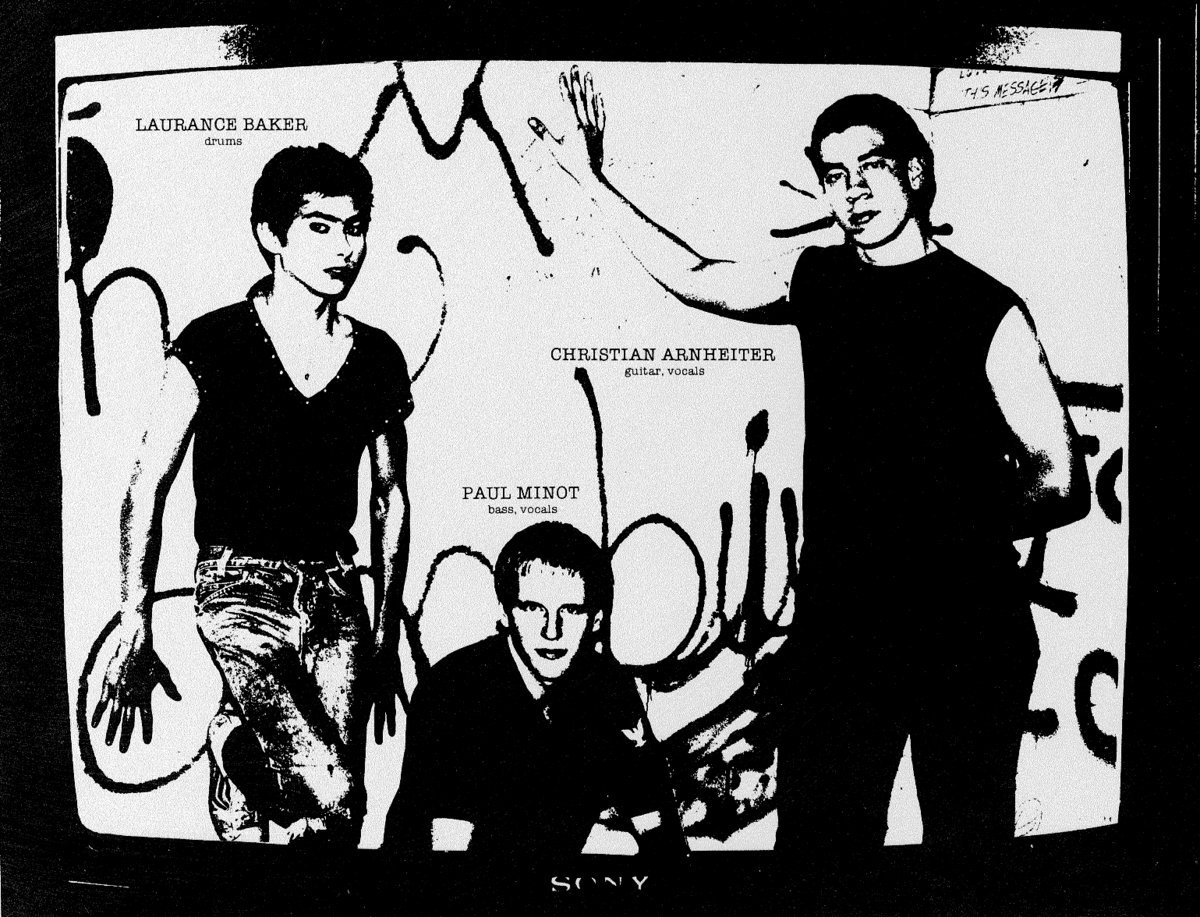

When I wasn’t practicing psychiatry, I spent a large part of my life playing bass guitar in rock bands–a substantial part of it writing, performing, and producing original music. The most noteworthy work I ever did was with The Hates, rightly billed as “Houston’s first and last punk band.” It was formed by a couple of friends with whom I had jammed occasionally while in college. Christian Arnheiter (aka Christian Kidd), guitarist and lead singer, wrote the music and lyrics; and Robert Kainer played bass. The band emerged in 1978, within a year after we had all seen the Ramones perform in Houston, and the Sex Pistols in San Antonio. The Hates released a few seminal vinyl EPs that were a cult success, leading to reissues of the tracks in later years—and have released many other recordings. Christian continues to carry the banner, and still performs in Houston regularly.

As a 4th-year medical student, I had the privilege of taking elective clinical courses at facilities across the country. In 1980, I took one such course in Houston—working for a month on a psychiatric ward called One South, in a prominent teaching hospital that will go unnamed. (This is not to be confused with the psychiatric ward “One South” examined in a recent HBO documentary, or any other.) This was an experimental unit driven by an academic model of “rapid tranquilization”—giving acutely disturbed patients very large amounts of psychiatric medication in a very brief period, to hopefully achieve rapid improvement. But the unit itself was a modern version of Bedlam—ten acutely ill patients in ten beds in one open room, with a couple of small bathrooms with single toilets, and no bathing options. Several nurses were placed behind a counter with no private area for them to work in. The only private room available was a smallish office shared between two or three social workers, and the medical student (me)—and nothing more. It was far and away the most nightmarish and maddening facility I’ve ever seen.

This philosophy of “rapid tranquilization” was driven entirely by psychiatry’s academic fashion of the day. The unit was the brainchild of a female academic at the affiliated medical school, and the promotion of medical interventions was entirely consistent with the neo-Kraepelinian revolution underway at the time. (I mention the professor’s gender only because the place was anything but maternal, and seemed more like the brainchild of some hardass Texas male.) The result was the most inhumane treatment that I have ever witnessed—not only for the patients, but for the nursing staff as well, because they were just about as trapped there as the patients were.

In those four weeks in Houston I learned a lot more about how I didn’t want to treat patients, than any constructive knowledge that I would apply today. But by this time Robert had left the band, so while in Houston I started playing bass for the Hates. I shared the above clinical experiences with Christian, and we co-wrote the song “One South” to document the experience. (Warning: This is a pretty damned raw live track with my own dubious vocals, recorded on God knows what in a nightclub.) However, Christian followed it up a couple of years later with a simply wonderful punkabilly track called “Texas Insanity”—calling attention to the reckless discharge of patients from Texas state hospitals without adequate outpatient support. He had another bass player then, but I had the honor of singing backup vocals while recording and co-producing this track in my home studio in Austin. Naturally, it was released as the title track of the album—because what punk album title could be more apropos than that?

The punk rock movement began as a reaction against the grandiose excesses of rock music in the early 1970s—album-long opuses with orchestral arrangements and pretentious lyrics. Ironically, what had previously brought Christian, Robert, and me together was our shared appreciation of such “progressive rock.” But all of us appreciated the opportunity to hop onto a more trendy genre that didn’t require classical music training, or the purchase of expensive keyboard setups and effects processors. “Punk” in those days was associated with bratty, provocative behaviors, most of it with tongue in cheek. However, there was of course a darker side to the scene—inviting the participation of people with destructive urges that might be directed at others, or themselves. (For those curious about what attracted “normal” people to the punk rock scene, I highly recommend the movie SLC Punk!)

But in the decades since, the word “punk” as an adjective has taken on the more positive aspects of that original scene—representing higher moral values in a way that few of us would have anticipated back then. I was stunned to find that an online search of the word yields the following description by Google AI:

The value of a punk perspective lies in its fierce anti-establishment, non-conformist ethos, championing individual freedom, authenticity, and DIY [do it yourself] spirit against mainstream culture, corporate control and authority, fostering creativity, critical thinking, and solidarity through raw self-expression and challenging social norms. It values questioning everything, rejecting hierarchies, promoting equality (anti-racism, anti-sexism), and finding meaning outside consumerism, empowering individuals to create their own paths and communities….The punk value isn’t just in rebellion, but in the constructive energy of creating something new and meaningful from dissatisfaction, whether it’s music, community, or a more just world, by refusing to accept the inadequate status quo.

I had no idea that Google AI was so hip, absolutely nailing the punk dream. And throughout the years that I’ve been pursuing the reform of modern psychiatric practice, I’ve been obsessed with three lines from a song written and performed by Elvis Costello—an English rocker actually labeled as “New Wave,” which was punk’s tidier brother. But these lyrics from his song “Radio, Radio” perfectly crystallize the broader and deeper definition of punk noted above, and have driven me forward throughout this personal mission:

I wanna bite the hand that feeds me

I wanna bite that hand so badly

I wanna make them wish they’d never seen me

It was psychiatry’s willful and persistent neglect of the CDC Suicide Study in 2018—documented elsewhere on this website, and in greater detail within my book—that made me ashamed and contemptuous of my own profession. The above words perfectly summarize the awareness that my dedication to this cause will make many of my peers unhappy, and that even success in this venture might bring me more personal loss than gain.